Testosterone isn't why men are violent

I knew with absolute certainty that I wanted to start testosterone. But a small part of me was afraid that the hormones that could save my life would also turn me into someone my old self would have been scared of.

[CW: mentions of suicide, transphobia, bioessentialism, and physical violence.]

I’ve never felt less violent since starting testosterone.

I’m still furious. I am so fucking angry, all the time. But that anger no longer feels violent. I don’t want to punch anyone, even the bigots and politicians who are stripping away trans rights and forcing schools to out trans youth to their parents and refusing to condemn a fucking genocide that we're watching happen in real time.

Every stereotype I’ve been told about men and testosterone – even my GP’s comments as before she agreed to let me have a bridging prescription for testosterone gel – suggested that I would get more violent on testosterone. I knew that it wouldn’t just be my body that changed when I started testosterone, but I stared to wonder if I really would become violent.

I hated the idea that I might. I knew that trans men are just as capable as cis men of being violent and benefitting from patriarchal systems; I knew that when I started to be read as a man I might make people feel uncomfortable or even unsafe. I can be loud and angry – aggressive, even – and have a propensity to talk about sex in graphic terms in public.

I try be aware of the male privilege I hold (though I’m sure I fuck up more than I realise), so when I started testosterone I readied myself to feel more violent. I was braced for the violent thoughts and urges I’d been told I would feel… but they never came.

Maybe it was because I was so depressed when I started testosterone. Maybe it was because the gel I carefully applied to my thighs and stomach on alternate days contained such a low dose that it took months for any changes to start. Or maybe, just maybe, we live in a society where we attribute men’s violence to their testosterone when it isn’t testosterone that is to blame at all.

Testosterone didn’t make me more violent, but it did make me question why we excuse men’s behaviour as though their testosterone levels mean they lack agency for their actions.

On a cold, wet evening in November, I played football.

It was the first time I’d played football in well over a decade, the first time I’d ever had fun on a football pitch. It was the first time I have felt comfortable playing any kind of sport. It’s not that playing football felt like an affirmation of my masculinity, it just felt joyful. I felt safe.

Many trans people know what it’s like not to feel safe when playing sports, but I was surrounded by trans people as I ran around on a football pitch in the rain. Trans Active (part of LEAP Sports Scotland, who work for greater inclusion in sports for LGBQTI people) ran ten weeks of all-ability football sessions in autumn 2023. While I was out of my comfort zone on the pitch, I was with my community.

Our coach was a trans woman wearing pink and leopard print football boots. “Stop being so nice to each other,” she yelled at us in the middle of one of the matches we played towards the end of the session. “This is a place where you’re allowed to get angry!”

I laughed when she said that. Trans women in particular are more harshly penalised for any display of anger. The misogyny of men telling women (or people they read as women) to smile, for example, is compounded by people taking a trans woman not smiling to be “proof” that she is not really a woman. (And of course, trans women cannot win, because if they do smile they are accused of upholding patriarchal systems.)

Trans people, like other marginalised groups, are expected to remain calm in the face of hatred and oppression. We are expected to respond politely when we’re called slurs and accused of being pedophiles. Almost any attempt to advocate for ourselves and our community – sometimes even our existence in public spaces – is labelled as violence. We are held to a standard that our cis people are not, while discussing topics that affect our lives and not theirs.

Throughout the football session, I slowly grew confident that I could (sometimes) make the ball and my body do what I wanted them to do. It felt so freeing to throw myself into something, not caring that I was bad at it. It felt freeing, cathartic, to not have to hide or hold back. How many chances do trans people get to do that, without our joy being read as violence?

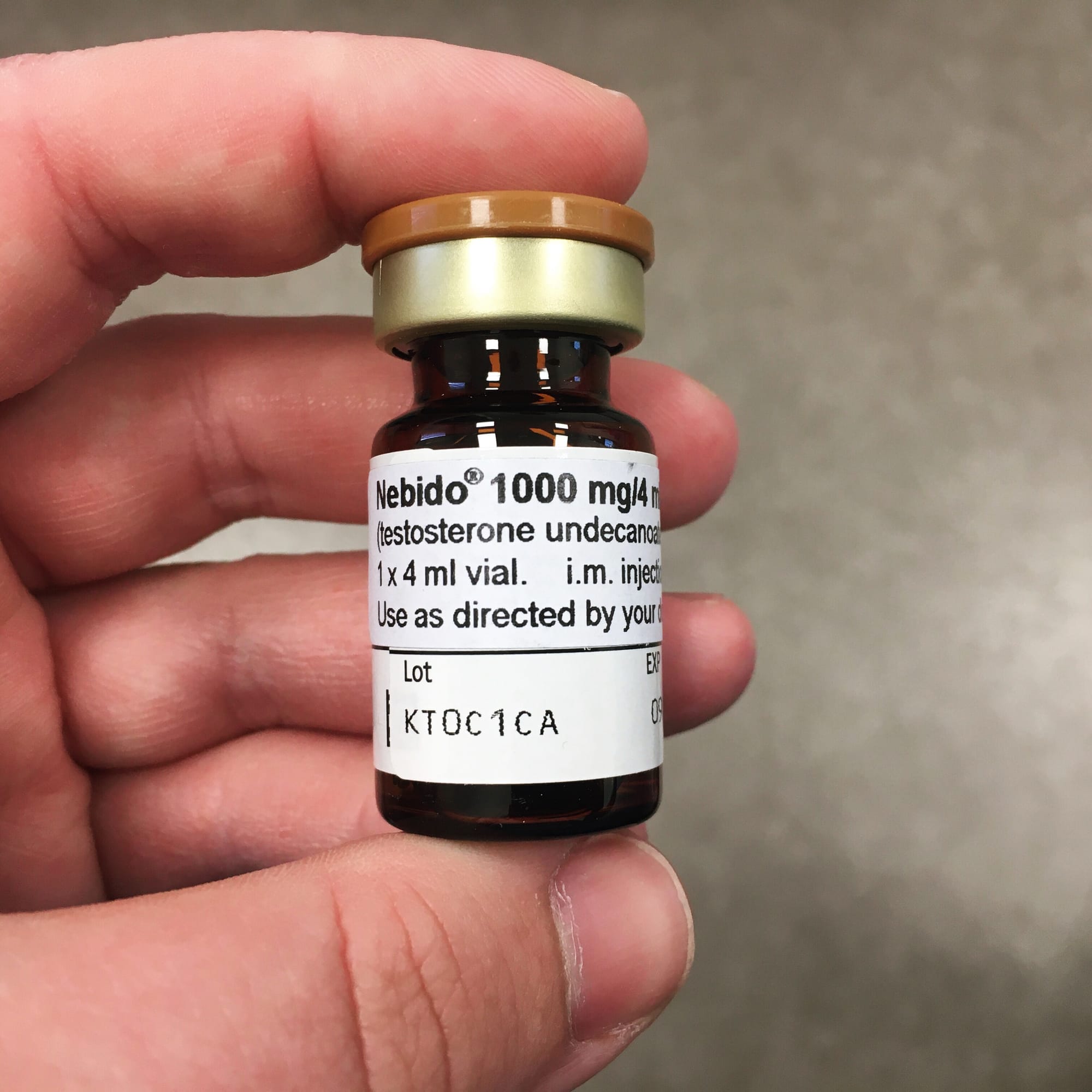

A few months ago, I was able to switch from testosterone gel to injections every three months. After years of waiting lists and jumping through hoops to access healthcare, it felt like all the changes I’d been carefully cataloguing since starting testosterone suddenly sped up.

I feel stronger now. The spurt of energy I’d heard other people talk about experiencing when they started testosterone finally arrived, albeit in a less powerful surge than I’d hoped for. But I still haven’t become more violent. If anything, I feel less violent than I used to. I am calmer, happier, and more in control of my emotions than I was before I started testosterone. (In some ways, this is unsurprising. We now have scientific research supporting what trans people have known for decades: that access to hormones improves our mental wellbeing and quality of life.)

Before starting testosterone, my anger used to feel violent. I would feel overwhelmed by the injustice in the world and utterly helpless in the face of so much pain. In my powerlessness, I felt violent, like that was the only tool that anyone ever listens to. I still feel powerless sometimes, but I don’t feel violent any more.

I sometimes still want to scream or direct violence towards myself, but that happens when I’m experiencing sensory overwhelm or in moments of self harm. It’s amazing to know myself well enough to link those things together now, and to understand the ways I can take care of myself.

When I feel those emotions rising within me, I know what to do. I sing Taylor Swift and Maisie Peters, Frank Turner and Bruce Springsteen. I read books that make me cry. I jerk off – oh boy, testosterone is really helping me make up for being too terrified to touch my own body until I was nineteen. I write, channeling rage and fury into my work. I apparently now play football.

Testosterone hasn’t made me more violent, even though my current testosterone levels would be too high to play football as a woman under the current FA guidance. But just as my masculinity is not dependent on my testosterone levels, it is also not dependent on my violence.

If violence was inherently linked to testosterone, we would surely see trans men becoming more violent when they start testosterone. Well, a meta-analysis published in 2021 looked at seven cohort studies with data from 664 trans men. It found that:

“The behavioural tendency to react aggressively increased in three studies out of four (at three months follow-up), whereas only one study out of five found angry emotions to increase (at seven months follow-up). In contrast, one out of three studies reported a decrease in hostility after initiation of testosterone therapy. The remaining studies found no change in aggressive behaviour, anger or hostility during hormone therapy.”

To me, that reads as decidedly inconclusive. (The authors of the paper point out that in all of the available studies, the follow-up period was less than 12 months and further research is needed.) And while I’m not saying that people taking testosterone do not experience changes in their emotions or behaviour, I think we do not only trans men but everyone a disservice when we assume that increased testosterone will make us more violent.

I wonder how much of the link between violence and testosterone – and indeed masculinity itself – is based in bioessentialist ideas that men are bigger and stronger and louder and more aggressive. While I’m undoubtedly ignoring any number of biological and psychological findings here, I can’t help thinking that men are more violent not because of testosterone, but because we expect and excuse their – our – violence.

After all, anger is one of the few emotions that men are permitted to have, and violence one of the limited ways they – we – are allowed to express it. I do not want to diminish the gross impact of men's violence or how men benefit from the violence of patriarchal systems, but they also police each other’s behaviour, forcing them to prove their manhood by falling in line with strict ideas of what ‘masculinity’ looks like. While I joke about my masculinity being fragile, cis men’s masculinity is very, very fragile.

I knew with absolute certainty that I wanted to start testosterone. I genuinely do not know if I would still be alive today if I hadn’t. But a small part of me was afraid that the hormones that could save my life would also turn me into someone my old self would have been scared of. Someone violent. The ways we talk about violence and testosterone made me wonder if that was inevitable.

It wasn’t. It isn’t. Testosterone didn’t make me more violent, it gave me the space and time and opportunity to become more self-compassionate. Far from being inevitable, violence –and, in fact, all of my behaviour and actions – have never felt more like a choice.

I do not need to prove my masculinity through violence. My masculinity can be soft and gentle and incredibly queer; I wish more cis men understood that theirs could be too. And I wish we could stop attributing men’s violence to their testosterone, rather than holding them – us – accountable.

- Most of the really good sex I've had over the last year happened with an episode of Taskmaster playing in the background. To coincide with the sixteenth series of Taskmaster, I wrote about the background noise people need during sex for Refinery29. While it sounds like a slightly frivolous topic, I think it's important to normalise how varied our wants and needs are during sex, because so many of us worry about whether we're doing sex "wrong". I hope this kind of piece encourages people to ask their partners for what will make sex good for them, even if that feels vulnerable.

- If you're curious, the trans porn performer I mention in this article that my girlfriend, my metamour, and I were watching during our NYE threesome was Cam Damage. Also shout out to my editor for this piece, Sadhbh O'Sullivan, for understanding my desire to include people of all genders and ensure the title reflected that and didn't misgender me or any of my case studies who were trans by labelling us 'women'.

- I also wrote about the reopening of the Vagina Museum and the importance of including trans people when we talk about gynocological conditions for Xtra. The Vagina Museum put in the work to ensure that their new exhibit, Endometriosis: Into The Unknown, included the voices and experiences of trans and non-binary people with endometriosis, and this article gives me something to share when I'm frustrated with people talking about these as solely "women's" health conditions. (I haven't made it down to London yet to visit the exhibit yet, but I hope to in 2024.)

- Elsewhere on Xtra, Ziya Jones (my editor for the piece above) and Kai Cheng Thom have written about why Palestine-solidarity is a queer issue and the way Isreal are using "pinkwashing" to justify their genocidal actions respectively. I recommend highly recommend reading both. I especially loved this section of Thom's article: "It is time for the queer community to stand up in the service of solidarity, political clarity and moral courage. We must not allow ourselves to be manipulated and exploited by pinkwashing—an ideology that was created not to protect us, but to shield atrocities from the light of truth."

- After listening to every episode of Maintenance Phase multiple times, I finally picked up Aubrey Gordon's book: "You Just Need To Lose Weight" and 19 Other Myths About Fat People*. Gordon is an incredible writer, and I love how the book isn't only trans-inclusive but explicitly addresses the anti-fat biases trans people face. And when I don't feel dysphoric, I find it a lot easier to challenge and start unpacking my own anti-fat biases. I especially enjoyed the chapter on how body positivity is often caveated with the term 'happy and healthy': "Capitalism is not and will not be a source of justice for any of us."

- On a similarly anti-capitalist note, I absolutely loved Rowan Ellis' video about the corporate commodification of queerness. It's brilliant and hilarious and Ellis speaks so articulately and emotively about issues with rainbow capitalism: "What does queer liberation actually look like? It's not white Skittles and free Subarus. It's not even just individual rights and equalities under the law. It's collective equality. Access to universal healthcare, housing and workplace protections, comprehensive education, a tackling of the current justice system and police force."

- Finally, Grayson Izekiel Colbert's 'PORTRAIT OF A TRANSSEXUAL' (2023) really speaks to how I'm feeling about my gender and medical transition right now. I love that I am intentionally making my body more my own every day.